|

« Back Abstract An artist, art therapist, and a member of Findhorn Foundation Community, Scotland, Beverley A’Court, gave an interview to Ecopoiesis Journal about her holistic, Earth-based approach to making art and practicing art therapy. She talks about the connection between art, therapy, and ecology, the role of the body as ‘an environmental phenomenon,’ and her use of nature and natural materials and objects in the art making process and in therapy. Key words: art therapy, body, environment, holistic, nature

Brief note about the interviewee: Beverley A’Court, BSc.Soc.Sci. (Joint hons. Phil. & Psych.), Dip. A.T. After a brief research career in Architectural Psychology, Beverley has been practicing art therapy since 1981, initially employed in acute and long term psychiatric services, learning disability, special and adult education, then pioneering holistic eco-art therapy via supervision, summer schools, and courses for professionals and students. As a long-term member of the Findhorn Foundation Community, she has contributed to international conferences, festivals and sustainability education programs, and developed many applications of eco-art therapy. She is an advocate for the recognition of the place of poetic language, the body, ecology, and cultural wisdom traditions in art therapy. A.K.: You have an artistic and art therapy background and were involved in ecological activism for many years. How can you describe the connection between art, therapy, and ecology? B.A.: As an artist, art therapist, environmental activist, and member of the Findhorn Foundation Community, the practical and even political question was and still is: How can an ecologically inclusive paradigm be applied in art and clinical art therapy practice? I rely on sensitive attention to the systemic interplay between the human being and the more-than-human environment, attuning to present-moment resonances between the authentic, expressive art-making and the activities of nature and wildlife. My journey in art and art therapy since the mid-1980s has been to acknowledge, explore and integrate these related streams:

The pre-historical, perennial roots of art were very much grounded in human beings’ relationship with the environments which they inhabited. All our perception and cognition arises within our embodied existence. From a bio-cultural, evolutionary view, the arts appear to have been effective instruments for attunement and adaptation to the natural environment, such as developing perceptual and cognitive skills in discernment for survival and for establishing socially bonding rituals. Ancient art works are often our only or primary window into understanding our ancestors’ lives, societies and beliefs. In addition, ethological perspectives on the arts help us to understand the role of the body as the focus of adaptive activities closely interwoven with ‘the behavior of art,’ as Ellen Dissanayake puts it. From stone tools, clay figurines, rock reliefs and cave paintings, from bone and horn puppet-toys, to ceremonial body ornament and costumes decorated with shells and stones, animal teeth, horn, fur and feathers, and later, metal jingles, and embroidered patterns of healing plants and dancing ‘goddesses;’ what we call 'arts and crafts’ were a core element of everyday life, where clothing and every implement had to be hand-made, mostly from locally sourced materials and worked with in a visceral, cooperative process. This suggests a quality of attuned attention, an embodied presence of mind-in-body in relation to materials, ‘mindfulness,’ eloquently described by contemporary therapists seeking to integrate into therapy and care non-dual, holistic wisdom from Eastern traditions and discoveries concerning neuroplasticity and global ecological imperatives. In environmental art and holistic art therapy, introducing natural materials and access to outdoor nature immediately stimulates action, interactions with nature; in art-making which vividly evokes and echoes the ancient traditional activities of our hunter-gatherer ancestry: selecting, gathering, wrapping, weaving and binding. The assembly of ‘fascicles,’ bundles of visually or symbolically similar or categorically disparate natural objects, which together have meaning and signify some kind of power, is a frequent initial response to the invitation to make art outside in nature. Figure 1"Talking sticks." Beverly A’Court. Painted and decorated natural objects As an artist and art therapist, through environmental practices I also have come to rely on my own body as a sensitive instrument of resonance to the natural field. I believe that body, mind and ‘environment’ are always present and interwoven in art-making and art therapy, but the complex dynamics and effects of their interactions have remained largely implicit in our theoretical analyses. The body, its place within the web of life, its structure and movement, though central in making and perceiving art, have not been regarded as such. I believe that the body plays a very important role in environmentally-sensitive, earth-based art and therapy. A.K.: Could you please explain the role of the body as ‘an environmental phenomenon’ in the art making process and therapy in more detail? B.A.: The following might be regarded as premises of a holistic art and therapy, in particular, holistic eco art therapy which I practice and have developed over the years:

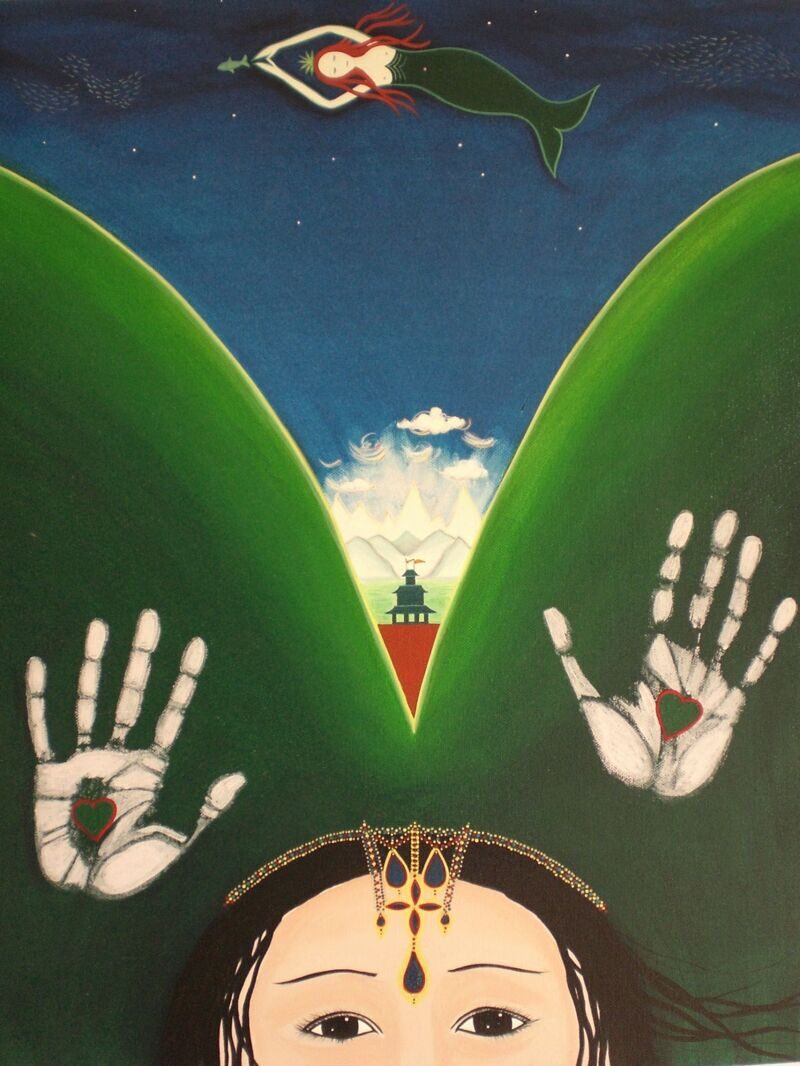

‘Health’ globally increasingly means multifaceted ‘well-being,’ a state of body-mind-world in which individual and collective vitality and opportunity is maximized in concordance with other living systems. In therapy this is typically manifested as awareness, ‘presence,’ the ability to remain a fully embodied, connected a compassionate, and attentive witness to self and others, amidst disturbance and distress. Images from many cultural traditions of the fulfilled, happy, 'enlightened,' or holy person often portray them within a complex natural environment, a landscape or garden, where they appear in peaceful harmonious existence with all life forms there, which are also in harmony with one another. The entire field is integrated, harmonised. The blessed person blesses the land. The footsteps of the holy person bless the path. A.K.: Could you please give an example of how the body is involved in art making and holistic art therapy? B.A.: The 'Gestural Drawing’ technique I often introduce evolved as a tool to mindfully explore the body’s inherent skeletal geometry and the natural gestural marks that emerge from resting in deep attention to this. It has become one among many forms of mindful, somatic preparation for outdoor eco-art therapy work as it invites authenticity within the micro-environment, the potential space of the large paper. ‘Drawing’ is facilitated to flow from the body as a form of non-doing, without direction and what Feldenkrais calls the 'white noise' of effort, contrivance and striving, while being witnessed as we monitor our felt sense. I also use 'breathing drawing' and the slow Tai Chi of writing-drawing your name as ways to meet the emergent authentic self with kindness and recognise its tendency towards harmony and both an 'emptiness' (of fixed, rigid identity) in a Buddhist sense, and meaning. Figure 2 “Green Tara." Beverly A’Court. Acrylic paint on canvas. Such exercises reveal and relax habitual attitudes of mental grasping at agendas, desires, identity and outcomes, facilitating a more open, receptive psyche-somatic state in which to experience and listen to both the body-mind and the field of nature. The process of ‘being drawn’ rather than drawing, resembles the being ‘drawn’ along, ‘called’ by nature to follow a path, towards or into an unfolding landscape. A metaphoric resonance, mirroring how we move through everyday life, is often felt in such moments. The rich discipline of Authentic Movement has been a long term inspiration to me in this exploration. The role of walking in the creative process and in therapy has its own traditions, often overlooked. Walking is associated with the rhythm and movement of mind and can be seen as a metaphor for how we move through the world. The power of walking to bring our body and creative mind into synchrony, to settle and awaken creativity in art, poetry and music, is testified to by painters, composers, poets, scientists and inventors. Walking facilitates loosening intensely focused attention on the logistics and mechanics of a problem to be fixed, in favor of a roaming awareness that scans the immediate bodily context and synthesizes diverse elements from experience, creating new images, associations, concepts and insights. Neurologically speaking, in relaxing our default attachment to pre-practiced, familiar verbal concepts, we are providing opportunities to allow new neuronal pathways to develop, entirely new thoughts that let us cognize beyond established boundaries. As far as therapeutic practice is concerned, in trauma work, for instance, the inclusion of embodiment within therapy can support the journey of recovery, for example in the use of somatic awareness practices to bring clients out of dissociation and post-traumatic flashback, providing short term ‘fast aid’ and longer term psycho-educational, self-help tools. Mindful body-environment awareness and eco-art exercises can support therapeutic aims by fostering reconnection, returning us to the ground of sensory experience, meeting ourselves and nature in the here and now, as an embodied self-system within a living, physical world-field. During art therapy, clients spontaneously relate physically to, or find ways to embody their art works, extending them into the space and environment via postures, gestures, then into slow movement and occasionally vocalisation before, during and after art-making or by making marks from subtly emergent impulses and expressive gestures. With permission and support, clients can learn to notice the subtle emergence of somatic changes. They may make images of specific body parts, sensations, symptoms or whole body experiences and follow urges to somatically express their imagery in facial expression, posture and movement, dance, song, and spontaneous prayer or poetry. Before, during and after art-making, clients can practice, here and now, embodying states unfamiliar or inaccessible to them in their everyday life and seek resonances in the natural world around them. A.K.: What particular environments, apart from working in the studio, do you use in your art and holistic art therapy? B.A.: We can extend the idea of the relational field around artist, client, and art therapist to include place and its inhabitants as significant contributors to our inner development and life. I use various natural environments, wherever I am working. In Findhorn I encourage clients to use the studio, surrounding garden, woodland and beaches, and to notice and include objects and life forms encountered there in their installations and constructions. Shamanic earth-based traditions, and many contemporary Indigenous societies, have always viewed the health of one person as interdependent with the health of all the systems in which they participate: family, land, animals, ancestors, and god-spirits of place. They respect nature’s ability to perceive and involve us and to ‘talk back.’ Fairy tales abound with whispering forests, talking animals, and saints and heroes who can converse with more-than-human life forms. Nature and her creatures, including our industrial surroundings, erupt into our awareness via loud sounds or sudden shifts of light/dark and other presences, at moments in therapy instantly recognisable to clients as precisely timed, marking a subtle inner impulse and amplifying its significance, or, during ceremonies, for example, as support for healing rituals. It is a reciprocal relationship: as art therapists we do not simply use nature merely as a passive scenic backdrop, exploitable for inspiration and resources. We attend to the relationship, to what happens between client and nature and to the client-art-nature-therapist field, just as many indigenous communities use ceremony and ritual to re-establish and harmonize the person-world relationship, often using the arts as the bridging medium. Figure 3 "Birch Shaman." Beverly A’Court. Natural and non-natural objects. In open door sessions, I invite the client, if they wish, to loosely include the garden in their awareness and to look and venture outside if, or when, they feel a ‘call,’ sometimes initially to go to a place that intuitively feels right for them. Invariably this place has some supportive or challenging meaning for them, and an encounter occurs which enters and colors their therapeutic process. Therapy itself, at times, becomes a narrative, in which causal and other significant non-causal, but significant, connections, appear. Complex, synchronistic field phenomena occurring during eco-art therapy, especially during the client’s art-making, can be observed to have a powerful catalysing and clarifying effect, ‘speaking’ directly to the client’s imagination. Figure 4 "Carbon Footprint." Beverly A’Court. Natural and non-natural objects. A.K.: Is it also possible or relevant for your art and art therapy to use some nature even while working indoors? B.A.: Yes, definitely, I advise arts therapists to do this, to include some living nature in the therapy space (even though of course it, we, are all ultimately 'nature'). Art therapists report that even a single flower or plant becomes a focus for attention and some kind of anchor in the natural world. For example, I keep a basket of driftwood forms, bones, shells, feathers and stones, on show and available during sessions both for my own art and for clients to choose to handle, to hold onto, especially when speaking of traumatic loss, and to bring some part of their awareness into the present, to awaken and nurture their senses and at the same time to invite subliminal wonder; where the wood came from, from what tree, bringing them ever more present in their bodies and connected to the wider sphere of the natural world. Forest trimmings and driftwood from the sea-shore embody the natural elements of the area, with their qualities as once-living material sculpted into organic forms by wind, sand and salt-water. Clients report comfort, warmth, softness and solidity from these objects, which often appear in the art works in various ways, symbolically holding physical and emotional experiences and memories. The ‘talking stick,’ carved with traditional symbolic forms and the antler horn-handled Scottish Highland walking stick and hazel or willow wands of Celtic tradition also often feature in clients’ art, crafted in distinctive ways expressive of the person’s emotional concerns and life needs. Some objects we find, or which find us (I call these 'given' objects and advise clients to choose these rather than take living plants, etc., for their creations), seem to be already ‘art;’ others we deconstruct and re-assemble to make art. Archetypal forms emerge from our interactions with found media: faces, figures, tiny houses, birds and ships are common, naturally dynamic shapes found in wind- and water-worn wood and stone. Bird-forms often morph into boats and vice versa. When we make art from found or given materials, there is often a feeling that they belong back in the world with work to do and should at some point be returned to nature or placed in another significant location. Often their final destination arrives in the mind as they are being made, and this becomes part of their meaning. Figure 5 "Ice Ship." Beverly A’Court. Natural and non-natural objects, gouache on paper. A.K.: How do you think your approach to art and art therapy is connected to the eco-human paradigm with its emphasis on the unity and co-creation of the human being and nature? B.A.: The holistic eco-human paradigm informing art and therapy is an alternative rationality with its own internal logic requiring appropriate modes of thinking and practice. Buddhist, pre-Buddhist and Taoist meditative, yogic and Western pre-Christian and Christian contemplative traditions have all informed my understanding and therapeutic approaches. We honor the ‘integrity’ of eco-art, valuing it as one of many non-verbal-conceptual forms of knowing, emergent from the communion of subjects, in the process of ‘making meaning’: the inter-subjective space, where the impulses of self-directing life forms meet and communicate. Honoring embodied experience and our clients’ creativity frequently challenges conventional perceptions and values, but art historically has carried this role and demonstrated great power to energize, liberate and evolve new perspectives on reality. Environmental art and art therapy offer opportunities to validate, and advocate for, forms of 'communion’ between sentient subjects; special relationships with the more-than-human world, characterised by recognition of a shared reality and a tenderness and intimacy that many people lack or marginalize in modern life. These experiences have a potential to restore a damaged sense of self, an 'eco-identity', and a power to contribute to the multi-faceted consciousness and well-being associated with inner and outer sustainability. Figure 6 "Arctic Circle." Beverly A’Court. Acrylic paint on canvas Holistic eco-art therapy invites and empowers clients to become their own eco-artist-healers, to attune deeply to their nature-within-nature for communing with nature’s vast field and to listen inwardly and outwardly for its song and find ways to express this. As global medicine increasingly includes eco-bio-psycho-social factors, art and art therapy assume a unique role in revealing the creative, healing self at work within the field of causes and conditions, potentially contributing to the reframing of many areas of care, attending to the root causes of body-mind and planetary conditions.

Note: Beverley’s works can also be seen on her website. holisticartherapy.wixsite.com/painthorse facebook page: Painthorse holistic eco art therapy. Introductory videos and workshop images. Some works and workshop images can also be found at: beverleyacourt.wordpress.com

About the interviewer: Kopytin Alexander Ivanovich Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Department of Psychology, St. Petersburg Academy of Postgraduate Pedagogical Education (St. Petersburg, Russian Federation)

Reference for citations Kopytin A.I. Interview with Beverley A’Court // Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice. – 2020. – Vol.1, №1. – URL: http://ecopoiesis.ru DOI: 10.24412/2713-184X-2020-1-70-77 |

In accordance with the Law of the Russian Federation on the Mass Media, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Communications (Roskomnadzor) on September 22, 2020, the web-based publication - The peer-reviewed scientific online journal "Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice" was registered (registration number El No. FS77-79134).

“Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice” is the international multidisciplinary Journal focused on building an eco-human paradigm, disseminating eco-human knowledge and technology based on the alliance of ecology, humanities and the arts. Our journal aims to be a vibrant forum of theories and practices aimed at harmonizing the relations of mankind and the natural world in the interests of sustainable development, the creation of Eco-Humanity as a new community of human beings and more-than-human world. The human being is an ecological being, not separate from the world. The Ecopoiesis journal is based on that premise and aims to develop a body of theory and practice within that framework.

The Journal promotes dialogue and cooperation between ecologists, philosophers, doctors, educators, psychologists, artists, musicians, designers, social activists, business representatives in the name of eco-human values, human health and well-being, in close connection with concern for the environment. The Journal supports the development and implementation of new environmentally-friendly concepts, technologies and practices in the various fields of health and public life, education and social work.

One of the priority tasks of the Journal is to demonstrate and support the significant role of the arts in their alliance with ecology and the humanities for the restoration and development of constructive relations with nature, raising environmental awareness and promoting nature-friendly lifestyles.

The Journal publishes articles describing new eco-human concepts and practices, technologies and applied research data at the intersection of humanities, ecology and the arts, as well as interviews and conference reports related to the emerging eco-human field. It encourages artwork, music and other creative products related to eco-human practices and the new global community of Eco-Humanity.