MEETING OUTDOORS: ALONE AND TOGETHER IN NATURE

Barbara Parker-Bell, PsyD, ATR-BC

Program Director, Art Therapy Programs & Associate Professor, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA

Nicole Rivero, Student, MS Art Therapy Program, Florida State University, USA

Sin Hui Lim, Student, MS Art Therapy Program, Florida State University, USA

Abstract:

This article was adapted from Dr. Parker-Bell’s keynote presentation which described her process of designing and teaching a studio art and self-care class to graduate level art therapy students at Florida State University during the COVID 19 pandemic. Due to the limiting factors of required online teaching platforms and virtual engagement, promoting self-care and connection through artmaking became a challenging objective. Consequently, Dr. Parker-Bell incorporated eco-art therapy components into the course design. Sixteen students were invited to select three eco-art therapy articles and explore represented eco-art therapy concepts in nature. Students opted to explore nature alone or together with instructor and peers if they remained in the Tallahassee area. Following nature experiences, students reflected and posted their artworks and reflective statements within the on-line class forum for witnessing by others and completed a paper. Instructor and student reflections about these nature-based experiences inform this article. Themes that emerged from reflections included increased awareness of the power of nature engagement to stimulate stress reduction, reawakened connections with nature and others, and generation of positive feelings related to viewing nature and working with natural materials.

Keywords: eco-art therapy, studio art, self-care, nature

As I reflected on the prospects of my role as an art therapy educator teaching a studio art and self-care course for Florida State University graduate art therapy students during the pandemic, I was initially daunted. How could I fulfil the teaching mission of fostering community and connection in a virtual space? How could I foster art exploration and supportive witnessing of artmaking processes when people were isolated at home? How could I encourage students to use their art for self-care during these difficult times? During that contemplative time, I turned to nature for inspiration and safety. When I explored nature alone and together with my students I found a place of peace and connection. At the end of our semester, a phrase arose and resonated with me, “While we lost much during the pandemic, nature could not be taken from us” [9]. Nature soothed our losses. Art helped us translate our experiences and forged a space for creative reflection. Connecting with nature and my students restored my sense of community and connectedness. The story of this 2021 class experience will be revealed below.

The importance of studio art & self-care concepts

The Studio Art and Self-Care Concepts class is offered at Florida State University (FSU) in Tallahassee, Florida Master's degree level art therapy students. This course was designed and added to the Florida State University Curriculum in 2018, one might ask, why does FSU have a studio art and self-care concept class as a part of their program? I will counter, the important question, why is self-care important for young and seasoned professionals to consider? In response, I offer this quote by Ashley Bush [2] who noted,

“Being a therapist is a bit like being a singer. The instrument is ourselves. We are responsible for the sound, the tenor, the timbre, the vibrato and the tone. Because of that, we need to keep our instrument, our presence, well cared for.” (p. 27)

Art therapy students select the art therapy profession to nurture others and provide a safe relational and creative space where growth may occur. Research has shown that clients value the therapeutic relationship and therapists who demonstrate warmth, empathy, reliability, humanness, and patience [8]. Yet, the intense demands and energy required to sustain attention, care, and creativity with clients require much from the art therapist. Work setting factors and pulls of life responsibilities add to demands mental health professionals experience, potentially contributing to personal depletion. Over the long term, lack of personal resource replenishment may erode a therapist’s interpersonal effectiveness and diminish the quality of the therapeutic relationship and lead to professional impairment [1]. If we are not well nourished, we cannot feed others. Returning to Bush’s metaphor, without self-care, the care of our instruments, we may be prone to letting off some pretty sharp tones, thus detracting from the experience of the listener. Self-care is an ethical responsibility. Learning and planning and practicing effective self-care strategies prepare art therapists for long and fruitful careers.

Studio art and self-care course goals

As noted above, the Studio Art and Self-care course goals addressed the ethical imperative of self-care and promotion of self-care planning. In 2021, we experienced the additional challenge of exploring and activating self-care strategies during pandemic times. While these goals were sufficiently ambitious given our world context, other established goals for the course were retained and addressed. These goals included exploring the role of art-making in the self-care process, reinforcing students' artist identity by providing a structure for students to continue creating art, and promoting students’ development and awareness of their own artistic language centering on the principle that the more an art therapist knows themselves and their own art language, the more they will be able to connect to the meaning of the artwork and the language of others. In this class we also explored the role of exhibition in art therapy and the dynamics of having others witness one’s artmaking processes and finalized artworks. With these important goals in mind, we worked together to cultivate a supportive studio community space where learning experiences could be accomplished.

Addressing pandemic realities

In prior years, the Studio and Self-care concept course was held in a sizable, attractive, and well-equipped studio classroom on the FSU campus and the richness of the class experience was partially dependent on the experience of making art in the company of peers and the instructor. However, in 2021 the pandemic policies and safety measures required us to offer the class on-line, even as we became hopeful that a vaccine would be lifting such requirements in the near future. Many students had also scattered to home locations far from Tallahassee, and we remained separated from the studio that we would have inhabited together. The new pandemic reality that students would join class from separate locations and connect to each other through computer technology required course innovations. My challenge was, how do I create a course that will help us be together and face these pandemic realities together while embracing our artwork?

In late December, 2020, as I sat at my computer, drank coffee, and planned my classes for the semester ahead, I daydreamed of energizing gatherings with colleagues where we could create art together and to talk about best ways to work. I fretted about the loss these opportunities and questioned my ability to generate this type of energy with my students in a digital environment. Yet, as I mused about my options, I looked out my window and saw nature beckoning me. These beautiful flowering camellia plants seemed to say, "Come outdoors. Meet outdoors. Let's be alone together in nature." At that moment, I embraced eco-art therapy experiences. I was heartened by the possibility of offering nature as a classroom. I envisioned students maintaining safe social distances, yet drawing in the air and smells of nature as well as its sights and sounds.

Figure 1. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Blossoming Camilla Flowers. [Photograph]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Embracing eco-art therapy learning: Alone & together

I established eco-at therapy learning goals for the course to be accomplished through readings, nature-based art experiences, and reflective writing. I invited each student to select three eco-art therapy readings from a variety of reading options. I then scheduled three class sessions at natural sites around Tallahassee and students were provided options for participation. Students could either join these in-person outdoor sessions while retaining safe social distancing and mask wearing, or they could elect to find an alternative nature location to explore if they did not feel safe enough to meet or if they were no longer located in Tallahassee. All students were encouraged to connect their eco-art therapy nature-based session explorations to their selected class readings. After each event, no matter if participation occurred alone or together, we posted our created or collected images and related statements into the virtual course learning space for the community to view. The following descriptions demonstrate how the semester events and responses unfolded.

Tallahassee Old City Cemetery

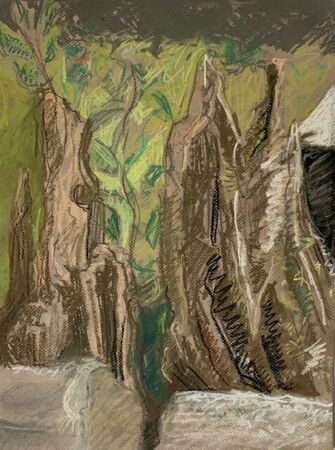

The first place the class explored was the Tallahassee Old City Cemetery. Even now, it feels somewhat surprising that we went to a cemetery, particularly during pandemic times. Truthfully, the cemetery was not our first choice, but due to circumstances we ended up at that location. This happenstance occurrence proved to be important for our reflections. During pandemic times, we have been surrounded by death. We have been worried about our own longevity and the longevity of our loved ones. We have felt isolated and yet, when we came to the cemetery, we felt connected with something beyond us. We felt connected with time, with nature, and the resilient cycle of life. In that regard, I took photographs of a tree trunk that had died but was also bringing forth new life. During my time at the cemetery, I sat in front of this trunk and found renewed spirit in its regeneration. I drew in nature and focused on rebirth.

It is important to note that while some students had seen each other on prior occasions during the pandemic, this gathering was the first time I had seen any students in-person in over a year. Therefore, meeting up with students felt rewarding even before our eco-art therapy explorations began. After greeting each other with brief conversation, we individually walked about the cemetery and found places to settle that would facilitate our personal eco-art therapy experiences. We remained socially distanced throughout most of the experience but came back together at the end of our session to report on our experiences before departing. I believe these connections at the beginning and end of sessions supported the heavy emotional content that was contemplated during art and nature experiences.

Figure 2. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Tallahassee Old City Cemetery. [Photograph]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Figure 3. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Rebirth. [Photograph]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Figure 4. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Rebirth Exploration. [Detail, Pastel Drawing]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Participating student Sin Hui Lim explained her response to engaging in an eco-art therapy experience at the cemetery and connecting her experiences to an eco-art therapy article as follows:

“I was so excited when I found a chapter titled “Environmentally and eco-based phototherapy: Ecotherapeutic application of photography as an expressive medium” by Kopytin [6] in the book “Green Studio”, which presents eco-based phototherapy. It helped me relate my photo-taking hobby to art therapy, as well as the environment.

During the mindfulness walking at the Old City Cemetery, I have the opportunity to increase my awareness of the five senses and reflect on the question that pops into my mind. ‘What should I do next in this uncertain situation?’ Being present and reflecting on the natural environment, I feel that life is a seemingly endless cycle. Regardless of joy or sorrow, it will not last permanently. No matter how much I wish to grasp it or get rid of it. I am just the small little tiny spot floating in the wind, which will eventually return to the dust. While ruminating on the meaning of life. I found the answer to my question. When I looked up, I saw a tomb written with the words, ‘I have kept the faith.’

I created a mandala using natural materials picked up from the ground for life cycle and self-reflection. This eco-art therapy experience reminds me of my forgotten passion for life and the courage for me to move on."

Figure 5. Lim, S.H (2021). Life Cycle. [Photograph]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Goodwood Museum & Gardens

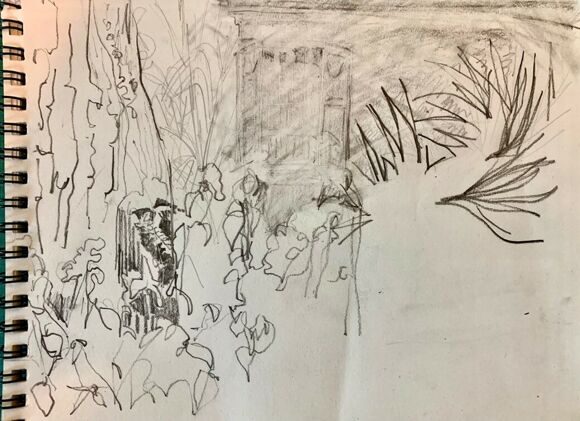

The next place we visited was the Goodwood Museum and Gardens in Tallahassee. This place is features beautiful natural settings but has a complicated history. In the 19th century, it was a family plantation and farm that utilized slave labor. When we visited this spot, there was more than just ourselves to contemplate, and in addition to nature, we had historical oppression and suffering to contemplate. These difficult facts pushed us to look beyond our pandemic experiences and concerns. Similar to the first event, each person explored and found a place within the site to enact our eco-art therapy experiences. Two of the three participants chose to draw from nature inspired by Jean Davis's [3] work. I was one of those people. I sat in this beautiful space, looking at one of the site’s buildings in the midst of beautiful old oaks and flowering bushes and sketched from nature. As Jean Davis [4] said,

“When one draws from observation, one is forced to truly see and experience the continual change that is nature, whether it's a rising sun blowing grasses, or shadows that grow longer and darker." (p. 66)

In this case, I also contemplated the relationships of those who farmed and lived in this place in addition to the surrounding nature.

Figure 6. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Goodwood Museum and Gardens [Photograph]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Figure 7 Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Plantation Building [Photograph] Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Figure 8. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Goodwood Gardens [Pencil Sketch]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Lafayette Trails - Heritage Park Tallahassee

Our final class trip was to the Lafayette Trails Heritage Park in Tallahassee. Here, I met with three students. We exchanged conversation briefly and then separately went to find spaces that resonated with us. The below photograph features the park’s beautiful lake and one of the fishing peninsulas where you can walk and immerse yourself in nature. Alternatively, if you so desire, you may follow tree-lined walking trails all around the lake.

Figure 9. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Lafayette Trail Heritage Park [Photograph]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Nicole Rivero, a student who participated in exploring the Lafayette Trail Heritage Park reported:

On this eco-art day, I met with a few of my classmates at Lafayette Heritage Trail Park. I used the article called Exploring Natural Materials: Creative Stress Reduction for Urban Working Adults by Chang and Netzer [3]. I walked around the park and settled down by the water to begin working on the first part of this process. I drew a reflection of how I felt as a student during a very busy and stressful semester, using pencil. After finishing this drawing, I decided to go on the walking trail of the park and look for natural materials for my next artwork. Once I found the natural materials I felt drawn to, I settled down somewhere else once more and created an art piece out of these materials. This eco-art activity helped me slow down and become more present. I realized how, in this fast-paced way of life I have had with school and deadlines, I have not given myself a chance to slow down and be mindful or immersed in nature. This eco- art therapy is something I definitely plan on continuing as a form of self-care, even after the semester.”

Related images are included below.

Figure 10. Rivero, N. M. (2021). Overwhelmed. [Drawing]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Figure 11. Rivero, N. M. (2021). Natural Expression. [Photograph]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

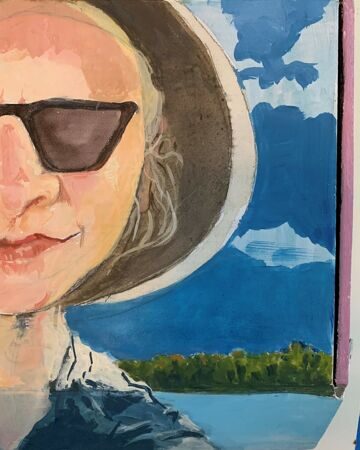

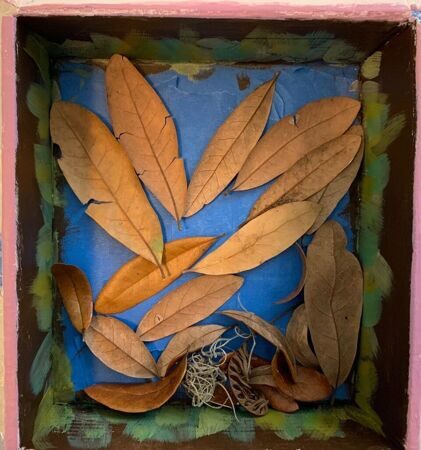

I too explored Lafayette Trails Heritage Park and connected with a different reading, Naor's [7] Expressing the Fullness of Human Nature Through the Natural Setting. I walked through the park and traipsed out onto that little peninsula and spread out my art materials; I felt connected with nature and began to appreciate my small presence in the much larger natural landscape. I considered the concept of the ecological self and the importance of my interconnection with nature. While doing this, I felt less alone in my experiences and more connected to an ever-continuing natural environment. I began a self-portrait on the outside of a box that I had brought with me. I collected natural materials from my journey, held them in this box, and returned home to complete the outer portrait and create an internal self-portrait, one filled with nature.

Figure 12. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Outside: Self-portrait with Nature. [Gouache and Acrylic Paint]. Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Figure13. Parker-Bell, B. (2021). Internal Self-Portrait with Nature [Mixed Media including Natural Objects] Tallahassee, Florida: Personal Collection.

Closing eco-art therapy assignments

Following the final eco-art therapy session, I asked students to summarize their experiences and explore their eco-art therapy learning in a paper format. Students were invited to identify eco-art therapy and nature-informed practices that particularly resonated with them and to identify which practices they would incorporate into their future clinical or self-care practices if any. In addition to more informal class discussions, these reports were instrumental in my understanding of students’ related experiences.

Conclusions

I believe the series of nature and art -based experiences were valuable to this small FSU art therapy educational community that consisted of 16 students. Based on students’ reports, postings, and dialogues, the main themes and outcomes related to students feeling more connected to their art, more connected with themselves, more connected with nature, and more connected with the group as a whole. Other students noted a decrease in their own stress levels and appreciated the knowledge of eco-art therapy concepts and applications. Many also noted that were they would likely use these processes within their art therapy practices in the future.

I asked participating students Sin Hui Lim and Nicole Rivero to reflect on their experiences one month following the end of the class. Based on their collective conversations, Lim and Rivero, felt that the eco-art therapy days allowed them to relieve stress and connect with others, nature, and themselves. They agreed that the nature-based experiences helped them become more mindful of felt experiences which fostered self-awareness. Both students also indicated that the class helped them realize the importance of meeting their self-care needs in nature. Although Rivero had not prioritized spending time in nature prior to this class, the eco-art therapy days stimulated her craving for nature-based self-care practices and experiences. On the other hand, Lim recalled that she had often explored nature in her home country, but when she moved to the United States, she found that she no longer took time to do so. This class helped her realize how important nature was to her and encouraged her to prioritize it again. Finally, the students’ reported recognizing the importance of continuing self-care and sustaining their connection to nature throughout their professional careers.

While I would not choose to re-experience pandemic circumstances, I am thankful for the conditions that moved me to explore new class structures and to add eco-art therapy concepts to the Studio Art and Self-care Course. Finally, I am grateful for experiencing nature’s solace in the midst of uncertain and challenging times.

Acknowledgements

I extend my thanks to Dr. Alexander Kopytin who provided me with opportunities to present these ideas to others, to Nicole Rivero and Sin Hui Lim for providing their permission to share their art and statements and for their contributions to this written text, and to all Studio Art and Self-care students who engaged in eco-art therapy class experiences during these pandemic times.

References

1. Abramson, A. (2021). The ethical imperative of self-care: For mental health professionals, it is not a luxury. The Monitor on Psychology, April/May 47-53.

2. Bush, A. D. (2015). Simple self-care for therapists: Restorative practices to weave through your workday. W.W.: Norton & Co.

3. Chang, M. & Netzer, D. (2019). Exploring natural materials: Creative stress-reduction for urban working adults. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 14(2), 152-168.

4. Davis, J. (2017). Drawing nature. In A. Kopytin & M. Rugh (Eds.), Environmental expressive therapies: Nature-assisted theory and practice (pp. 123-160). New York: Routledge.

5. Hinz, L.D. (2019). Beyond self-care for helping professionals: The expressive therapies continuum and the life enrichment model. New York: Routledge.

6. Kopytin, A. (2016). Environmentally and eco-based phototherapy: Ecotherapeutic application of photography as an expressive medium. In A. Kopytin and M. Rugh (Eds.), Green studio: Nature and the arts in therapy (pp. 155-178). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

7. Naor, L. (2017). Expressing the fullness of human nature through the natural setting. In A. Kopytin & M. Rugh (Eds.) Environmental expressive therapies: Nature-assisted theory and practice (pp. 204-225). New York: Routledge/Taylor&Francis

8. Norcross, J.C., & VandenBos, G.R. (2018) Leaving it at the office. A guide to psychotherapist self-care, (2nd Ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

9. Parker-Bell, B. (2021, May 7). Meeting outdoors: Alone and together in nature during pandemic times. [Keynote presentation]. 24th Annual Conference: Arts Therapies Today: Arts Therapies in Education, Medicine, Social Sphere, Online.

Reference for citations

Parker-Bell, B., Rivero, N.M., & Lim, S. H. (2021). Meeting outdoors: Alone and together in nature. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, 2(2). [open access internet journal]. – URL: http://en.ecopoiesis.ru (d/m/y)