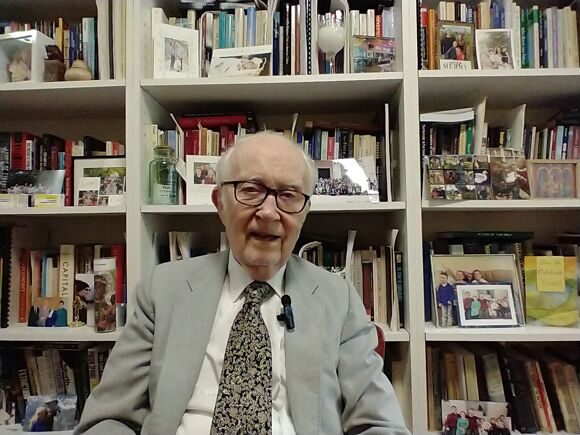

INTERVIEW WITH JOHN COBB

Abstract

In an interview, an American theologian, philosopher, and environmentalist, Dr. John Cobb talks about the ecological civilization and his perception of the ways to build it. He develops his thoughts on religious pluralism and interfaith dialogue, as well as the need to reconcile religion and science and to build what he calls Earthism, and how to develop a more sustainable future by replacing the national and global market by local economies.

Key words: ecology, ecological civilization, theology, religion, Earthism

Brief note about the interviewee:

John Cobb, is an American theologian, philosopher, and environmentalist. Cobb is regarded as "one of the most important living philosophers residing in the West"(Andre Vltchek). He is also a member of American Academy of Arts and Sciences. As the preeminent scholar in the field of process philosophy and process theology, the school of thought associated with the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, Cobb is the author of more than fifty books. A unifying theme of Cobb's work is his emphasis on ecological interdependence—the idea that every part of the ecosystem is reliant on all the other parts. Cobb has argued that humanity's most urgent task is to preserve the world on which it lives and depends. Because of his broad-minded interest and approach, Cobb has been influential in a wide range of disciplines, including theology, ecology, economics, biology, and social ethics. In 1971, he wrote the first single-author book in environmental ethics, Is It Too Late? A Theology of Ecology, which argued for the relevance of religious thought in approaching the ecological crisis. In 1989, he co-authored the book For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy Toward Community, Environment, and a Sustainable Future, which critiqued global economics and advocated for a sustainable economics.

Cobb is the co-founder and co-director of the Center for Process Studies in Claremont, California. Process philosophy in the tradition Alfred North Whitehead is often considered a primarily American philosophical movement, but it has spread globally and has been of particular interest to Chinese thinkers. As one of process philosophy's leading figures, Cobb has taken a leadership role in bringing process thought to the East, and thus made a significant contribution to the China’s move to ecological civilization. He was called "Eco-Sage of Our Time" in China. With Zhihe Wang, Cobb founded the Institute for Postmodern Development of China (IPDC) in 2004, and currently serves on its board of directors. Through the IPDC, Cobb helps to coordinate the work of 36 collaborative centers in China, as well as to organize more than 100 conferences on ecological civilization.The Claremont International Forum on Ecological Civilization is the best known one which started in 2006. It is the earliest and the largest forum on ecological civilization in the West. The 15th Claremont Eco-Forum held in 2022 reached out to around 15 million reviewers via various traditional and web-based media.

Alexander Kopytin (A.K.): In 1971, you wrote the first single-author book in environmental ethics, Is It Too Late? A Theology of Ecology, which argued for the relevance of religious thought in approaching the ecological crisis. Some people believe that world religions are a part of the problem since they, in particular, maintain human superiority above nonhuman animals. What is the relevance of religious thought in approaching the ecological crisis? Is it possible to interpret the world religions on the basis of connectivity ontology, of the dialectic of recognition and of a broader concept of justice that includes both human and non-human life. Do you believe that the dialectic of recognition based on the capacity for people to recognize and appreciate other human and non-human life forms as other subjects sharing with them a common world is one of the steps to bring world religions to the forefront of ecological movement?

John Cobb (J.C.): Presumably prior to civilization humans were part of the vast ecological system. When people began building cities and organizing society around them, they disrupted the natural ecology. Their religious lives were bound up with this change. In my periodization of history, the next significant development was the axial period. All around the world human mental life began to objectify itself. Individuals thought about thinking and how it was related to action. In Greece it produced philosophy, but left traditional forms of religion alone. In Israel it affirmed the reality of a Creator of all things who calls for the ultimate loyalty of human beings. The focused shifted from how we deal with the natural processes of life to what is asked of us by God and how that is related to Earthly powers such as kings. This can be called religion. In India Hinduism and Buddhism developed out of a combination of critical reason and mystical experience. In China Daoism stressed the relation to the natural world while Confucianism caused Chinese to be highly reflective about societal relations. Whether these are all religion or are additional to religion or substitutes for religion has never been clear. But all of them tended to redirect attention still further away from the natural dimensions of human existence to what humans can create and choose. The next great change took place with the rise of modern science and industrial production. These placed human knowledge, desires, and goals in the center and organized life around them to a new degree.

Evolutionary thought in principle calls for deep changes in the human relation to the rest of nature, and ecological thinking is coming into being. Thus far its role is marginal. Human control over everything remains primary in determining our thinking and acting. However, there does seem to be on the rise a new religiousness that we might call Earthism that can either function as an alternative to the inherited religions and philosophies or a modification of them.

A.K.: What do you mean by the term "Earthism? How would using this term affect our view of the reationship of human beings to the rest of nature?

J.C.: By "Earthism" we mean, of course, that our inclusive concern is the planet we inhabit. In purely theoretical terms, this seems arbitrary. Our explorations have already gone beyond the Earth. The wellbeing of the Earth depends on the wellbeing of the solar system and even more. Nevertheless, some find it, in a practical way a good compromise between utter inclusiveness and the excessive narrowness of nationalism and even humanism. It can make convincing claims over against those more common forms of supreme commitment. In other words, commitment to the wellbeing of the Earth is understandable and persuasive. It makes an enormous difference. One need not argue against anyone's extending concern and commitment to the rest of the solar system, but the difference that would make is extremely slight. On the other hand, the difference that concern for the whole planet makes in relation to primary commitment to the wellbeing of one's species or nation is obvious and obviously important. Also, the Earth can be presented as something to be loved and served, something beautiful and generous, and something on which we are utterly dependent. Children invited to devote themselves to the well-being of the planet will understand what it means and how it transcends most of their loyalties and commitments.

I am myself a theist. By understanding the whole as caring and acting for us and calling us in principle to care for the whole of creation, I go beyond Earthism. But for many people, neither the universe nor God is a meaningful object of devotion. Many simply abandon the goal of devoting ourselves to an inclusive whole and simply seek money for themselves and those they care for. The consequences will be sheer disaster for us all if we cannot do better. I recommend nations pointing their people beyond themselves to the Earth. In that sense I am an Earthist. This could be the deepest goal of national education.

A.K.: Your interdisciplinary search is very impressive. Due to your broad-minded interest and approach, you have been influential in a wide range of disciplines, including theology, ecology, economics, biology, and social ethics. What role does ecology play among them?

J.C.: Since the philosophy I adopted has this Earthist character and provides a different way of viewing everything, in principle adopting the philosophy and its religious implications calls for changing thinking about everything. To begin with it calls in question the fragmentation of scholarship into academic disciplines. It calls for thought to be focused on issues of importance to the world and all its inhabitants, and these questions cut across disciplinary boundaries. But since scholarship is now organized in terms of disciplines, it often has to begin in one or more disciplines. I prefer to think of my work as nondisciplinary, but it often takes the provisional form of being multidisciplinary. In my opinion no really important question lends itself to treatment as belonging to a discipline. Contrast the organization of a college around great books and around academic disciplines.

A.K.: Do you believe that ecology as a transdisciplinary field of knowledge can help us to develop the forms of thinking required to reassess the relationship between humanity and nature and between individuals and their communities, and thereby to transform the way people live and organize themselves, to provide the basis for a different vision of the future, with a different kind of ethics and political philosophy than those which have dominated modernity?

J.C.: The fact that I am doing what I can to promote ecological civilization is an indication that my support of Earthism takes this form. Much of what is wrong with modernity is that its materialist, individualist models are profoundly ethically and spiritually and even politically and economically destructive. Philip Clayton proposes to China the affirmation of organic Marxism. Its advantages even in science are dramatic. Some of us think that Alfred North Whitehead provides us with an organic philosophy that, if adopted in capitalist countries, would transform them in the direction of an emphasis on communities and communities of communities. We are not committed to one size fits all. But we are committed to the fact that we all need to understand our dependence on others and seek the good of all. Ecology gives us many examples of diverse organizations in the natural world. We depend on them and can experiment with different forms of human community and different ways to integrate human communities and natural ecologies.

A.K.: A part of ecological crisis, as I see it, is a crisis of human knowledge and ‘humanistic exhaustion’, the loss of belief in humanity and its ability and will to serve as the conscious and intentional source of agency. My impression is that the humanities are dramatically losing their historical raison d'être of cultivating the humanity in human beings and are increasingly turning into a scientific field which is more preoccupied with how to control and pacify people. Postmodernism, with its characteristic relativism and skeptical attitude towards the human foundations of culture, has contributed to this crisis of humanism. The crisis of the humanities and advent of posthumanism appear to be one of the consequences of the introduction of NBICS technologies (nano-, bio-, info-, cogno-, socio-technologies) together with systemic cultural causes. Do you recognize any problem in the humanities in their relation to the ecological crisis today? What relation does it have to postmodernity and the posthuman perspective? What do you think could be a solution of the problem helping to overcome a crisis of human knowledge? Will ecological thought be involved in that?

J.C.: Humanism emerged in the axial period. It was inherently religious, that is a system of values centering on human ones. When I use the word "values" I refer to what is judged of great importance. Religions support values and values support religions. These mutual supports are not purely rational. Often feelings are valued more than opinions.

As religious commitments become a problem to political authorities and as their diversities lead to conflicts among them. They come to be disvalued. Science provides a way of simply getting facts straight. This "secular" approach seems better. So, education is secularized. The academic disciplines are value free.

Humanism benefited from the move toward secularism, but the ideal of being value free undercuts it. As a powerful movement, it too is religious. What is left when it loses that dimension is of little interest. Teaching facts about values without valuing that teaching has little future. Furthermore, to turn to humanism when we are just truly appreciating the importance of the integrated Earth system will not help us.

A.K.: What do you mean?

J.C.: The heart of humanism is to reverence, support, and promote what we find most important in the human. It accents what is distinctive about human beings, and unless is qualified quite drastically, tends to treat other living things as valuable only in their contribution to us. Of course, humanism could be redefined as including the great value of the rest of the natural world and humans giving disinterested commitment to the wellbeing of the nonhuman.

A.K.: As one of process philosophy's leading figures, you have taken a leadership role in bringing process thought to the East, and thus made a significant contribution to the China’s move to ecological civilization. Together with Chinese colleagues you founded the Institute for Postmodern Development of China (IPDC) in 2005, and serve on its board of directors. Through the IPDC, you help to coordinate the work of many collaborative centers in China, as well as to organize annual conferences on ecological civilization. What place does the notion of ecological civilization occupy in your thought and activities? Since ecological civilization is differently understood by different people I would like to know, what ecological civilization means for you?

J.C.: Process thought integrates thinking and acting. However, there was no clarity about the alternative world for which it was called. The Chinese used the term "ecological civilization" as a name for what is needed now to incorporate humanism in a much larger context. They saw connections between the goals implied in process thought and ecological civilization. Many of us thought it was just the right term. The term civilization made it clear that this was not turning our backs on the amazing achievements of human beings, but whereas in the past they have tended to depreciate the natural world, calling for an ecological civilization made it clear that humans were part of something much larger and would destroy themselves if they did not attend to the larger whole.

A.K.: I think that ecological thought is a fundamental challenge not only to the core assumptions of modern science, but of industrial civilization as a whole. Acceptance of ecology involves not merely a transformation of science, but a transformation of the relationship between science and other domains of culture, impacting on people’s lives, their institutions, and their organizations, and more fundamentally, on their image of the future and of the ultimate ideals and goals worth struggling for. Recent developments in ecology What do you recognize as a most significant contribution of recent developments in ecology and process thought to ideology of ecological civilization?

J.C.: Appreciating that we must concern ourselves with the larger whole even when that gets in the way of narrowly human goals is a profound religious change. I cannot say that it has taken place, but here and there it is taking place. It is affecting public thinking. A major obstacle is that the university is organized in very anti-ecological way. I am disappointed the university brings up the rear on intellectual/cultural/spiritual change. What little influence process thought has attained in academia is being used to end this situation.

A.K.: When we speak about ecological civilization, we believe that the current, or industrial civilization and the modern consumer society, is exhausted, or nearly exhausted and requires radical systemic changes that embrace both economy and people’s mindsets, how they treat and understand themselves, each other and non-human animals, the environment, the Earth. No purely technical means will help us to come out of trouble. Either humanity will continue on a path of degradation, or it will have to qualitatively change the very nature of civilization, and hence the structure of universal human values and the social nature of society. What steps, do you believe, are needed to come to ecological civilization?

J.C.: Since the change is fundamental cultural/spiritual, those are the fields. But since the world is fundamentally ruled by economics, that may be the most important battlefield.

A.K.: In 1989, you co-authored the book For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy Toward Community, Environment, and a Sustainable Future, which critiqued global economics and advocated for a sustainable economics. What we could do with the globalized market economy today, in its connection with notions of liberal democracy, in the form of modern neoliberalism, since they demonstrate their inability to cope with the key challenges of our time, such as preserving the global ecosystem and human preservation, fair interstate relations and peace? Do you believe that some new constraints of thought and action in taking into account the freedom and significance of others (both human and non-human beings) are necessary in our quest for justice and the proper understanding by the human component of the ecosphere?

J.C.: I do not know what it will take to persuade academics to open their minds and re-think. Unfortunately, in the general culture the reality is so threatening that very few are psychologically able to attend to it. Bonnie Tarwater has persuaded me that we need to make available support groups that would help individuals to acknowledge reality and help one another make the changes for which it calls.

A.K.: Is it necessary or even possible to free people from enslavement to the laws of the market by subordinating markets to communities, reducing markets to instruments serving these communities? What superior ideals, apart from those propagated by neoliberalism and market economy would be necessary to overcome the seductions of consumerism and liberalism.

J.C.: "The national and global market" must be replaced by local economies as fundamental. People must see the connection between their actions and the resulting conditions and think in terms of how to achieve a healthy community even with far reduced use of scarce resources.

Stephen K. Levine (S.L.): Does your viewpoint take into account what is designated by the term Anthropocene? How would this concept of the Anthropocene affect our view of nature?

J.C.: I have not made much use of the word "anthropocene." I have understood it to point to that period in human history in which it is assumed that human beings are in charge and that those who use the term are generally supportive of this arrangement. I have thought that it is much better for human beings more often to adjust to the larger natural context rather than to try to force the rest to adjust to us. Of course, I enjoy many of the consequences of human control. I can be comfortable however hot it gets outside. However, we are learning that our taking control has led to the great increase of forest fires that we do not control. It seems likely that forest cover is destined to decrease despite all our efforts and that global temperatures will continue to increase with accompanying dismaying consequences. To me this implies that the idealization of human control has misdirected our actions. But if the term merely refers to the fact that most of what happens now results from human activity, this is certainly true. I would be glad to participate in discussion about what people mean by this term and the ways they use it. I write with no authority.

S.L.: What does China have to offer in terms of our understanding of ecological civilization? Considering the impact of the current centralization of power in China and decisions that are made by that central committee, particularly by Xi, what does China have to offer in the development of an ecological civilization that would be different from other countries?

J.C.: A major reason that human domination of the planet has had profoundly threatening consequences is that the West defines its goals chiefly in terms of money. Most Western governments are largely controlled by corporations and their immediate interests. China certainly has produced powerful corporations, but the government of China remains in control and sets its goals independently. This means that it does not require independent support from corporations in order to support ecological civilization. It has in fact given ecological concerns a great deal of attention. If the United States ceased to push towards war, we could hope for more.

S.L.: The Chinese philosophy of Daoism has a different conception of the relationship of human beings to nature than Western philosophy. Can such a perspective be helpful to our understanding, especially since in China it has always been a minority perspective and continues to be such? How could we integrate it into our conception of ecological civilization?

J.C.: Chinese interest in maintaining and developing Chinese culture and traditions is real and is playing some role in many aspects of contemporary Chinese life and policy formation. Taoism and Confucianism are the two main currents that are regaining influence. Both have great advantages over the dominant contemporary forms of Western modernism. Emphasizing Chinese values serves to moderate the destructiveness of industrial thinking and expansion. The world needs examples of coherent thinking about society and its natural context. This needs to be based on the rejection of individualistic substance thinking. Chinese traditions offer much possibility. We Whiteheadians hope that Whitehead's demonstration that individualistic substance thinking is damaging to science and that something closer to traditional Chinese thought could liberate science for new advances will strengthen efforts along these lines.

A.K.& S.L.: We highly appreciate an opportunity to talk to you.

Interviewed by:

Kopytin, Alexander

Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Department of Psychology, St. Petersburg Academy of Postgraduate Pedagogical Education (St. Petersburg, Russia)

Stephen K. Levine

Ph.D., D.S.Sc, REAT, Professor Emeritus, York University (Toronto, Canada), Founding Dean of the Doctoral Program in Expressive Arts at The European Graduate School (Switzerland)

Reference for citations

Kopytin, A., Levine S.K. (2023). Interview with John Cobb. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, Vol.4(2). - URL: http://en.ecopoiesis.ru