THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS OF SOCIALIST ECO-CIVILIZATIONAL PROGRESS

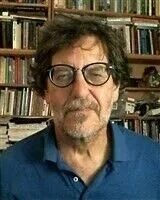

Arran Gare

Assoc. Prof., Philosophy and Cultural Inquiry, Swinburne University of Technology (Hawthorn, Australia)

Abstract

The quest to create an ecological civilization has been promoted for the most part by eco-Marxists committed to creating some form of eco-socialism. It is suggested in this paper that what is meant by all these terms is problematic, but they can be clarified by defining them through concepts deriving from ecology, and as such, the quest for ecological civilization can be seen as the quest to develop and realize an ‘ecological culture’, taking ecology as the root metaphor for comprehending the whole of reality. It is argued that the concept of ecopoiesis, deriving from ecology, provides a bridge between the natural sciences and the humanities, providing the basis for the reformulation of the social sciences and political philosophy required to create a new world order, an order that is committed to augmenting the life of the biosphere and human communities at all levels, while facilitating the comprehension of humanity as part of nature required to achieve this. In the immediate future, this project involves defending the United Nations and upholding the rule of law internationally, integrating the quest for a multipolar world-order with the quest for a global ecological civilization.

Keywords: ecological civilization, multipolar world, eco-Marxism, ecological culture, ecopoiesis, political philosophy, United Nations, rule of law

Introduction

A problem with the quest for an ecological civilization is that there is no consensus on what these two terms mean, and without this consensus, offering the theoretical foundations for ecological civilization is also problematic. To simplify things, I will align myself with those who see ecological civilization as a global civilization based on a very different relationship between humanity and nature than presently exists. To simplify matters further, I will take eco-Marxism working towards eco-socialism as a point of departure. Even this is problematic, as there are so many different interpretations of Marx, and Marx himself said if there is one thing that he knew, it was that he was not a Marxist, and socialism means very different things to different people. However, I believe a careful reading of Marx in conjunction with the work of the eco-Marxists points to what is crucial, and justifies seeing ecological civilization as a development of eco-Marxism in the quest for socialism conceived of as subordinating markets to communities to unite humanity in all its diversity.

The contributions of Marx and eco-Marxism

Marx, following and building on the work of Sismondi, had identified and analysed the dynamics of a new socio-economic formation, later labelled capitalism, that originated in Western Europe, and having established itself, by its own logic had to expand and grow until it encompassed the entire world. This is the era of modernity. The ultimate goal of human activity in this formation is not producing goods that are useful, but the growth of capital, requiring a return on capital investments greater than the capital that has been invested, although this is underpinned and integrated with a vision of the future in which ruling elites will have total technological control of nature and people. All other human activities and nature itself are understood and evaluated in terms of facilitating capital accumulation and the technological control required to achieve it. If useful things that benefit humanity are produced in this process, this is incidental. This way of thinking presupposes and advances commodification through which items in the world are evaluated in terms of their exchange value, and this formation has driven commodification extensively, to encompass the world, and intensively, commodifying more and more aspects of reality. The result is a highly dynamic system. As Marx and Engels put it in the Communist Manifesto [26, 475f.), it is characterized by:

‘Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all newformed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air.’

The eco-Marxists, Patel and Moore [30], have shown how this drive to capital accumulation involves the constant drive to cheapen the cost of inputs, whether labour power or natural resources. This has resulted in these inputs, including people, being conceived as objects to be controlled efficiently by agents who initially saw themselves as outside nature. Patel and Moore show that right from the beginning the quest for cheap labour and materials was associated with imperialism, initially to provide slaves for plantations and cheap land and materials. Both slaves and the materials extracted were quantified and processed as nothing but objects. This objectification of reality, associated with commodification, paved the way for the atomistic, mechanist view of nature, society and people promulgated in the Seventeenth Century scientific revolution, which provided knowledge of how to achieve technological mastery of the world, although blinding people to the destruction of the processes within nature and society required for this technological control and for the economy to function. This mechanistic world-view was often conjoined with Cartesian dualism in which the masters conceived themselves as fundamentally different from and outside the world they were dominating. Cartesian dualism was largely superseded by Darwinian evolutionary theory and Social Darwinism characterizing evolutionary progress as the domination by the powerful of the weak and the elimination of the weak, with organisms, including humans, conceived as complex machines, and the more powerful, as better, more efficient machines. This came to be known as the scientific world-view, implying beliefs with a claim to truth very different from and much stronger than those claimed by other societies or by the arts and humanities (which Thomas Hobbes argued, are nothing but rhetoric or entertainment). The human sciences were modelled on and designed to be consistent with this mechanistic world-view, beginning with what became mainstream economics, which was further defended through Darwinian evolutionary theory, and then the other human sciences. In this form these human sciences were also embraced as part of the scientific world-view [37]. This world-view, or rather, world-orientation, then legitimated and contributed to advancing the socio-economic formation that engendered it [8].

Imperialism associated with capitalism gave birth to what Immanuel Wallerstein called the world-system, differentiated into core zones, semi-peripheries and peripheries, where the core zones dominate the semi-peripheries through comprador elites, using them to exploit the rest of the population and the peripheries. Within this system there is constant struggle by countries and regions, often associated with wars, to rise within this system. The most violent wars are associated with struggles in the core zones for global hegemony, as when Britain replaced the Dutch Republic, defeating France, and USA replaced Britain, defeating Germany. The eco-Marxist Stephen Bunker, through his study of Brazil and Amazonia utilizing Richard Newbold Adams energetic theory of social power -- according to which power is control over the meaningful environment of others, showed how this structure has engendered destructive exploitation of the peripheries for their natural resources, creating hypercoherent ruling elites so powerful that they can and do ignore the destruction they are causing to those they are exploiting and, ultimately, to their own environments. They are now destroying the global ecosystem. This is the world order in place at present. Ultimately, it is a world order driven by the quest of ruling elites for capital accumulation and world domination, where capital is power and where whatever is profitable is ecologically unsustainable, and whatever is ecologically sustainable is unprofitable.

From eco-Marxism to ecological сivilization

With this background, what can we say about the notion of civilization, and then the notion of ecological civilization? The notion of civilization has diverse meanings and ambiguous connotations. It implies a development beyond barbarism, as an achieved condition of refinement and order. However, it is also associated with the conquest and enslavement of others who provide the conditions for the development of ‘high culture’, and eventually decadence. And then the term is used to characterize particular societies as civilizations – Ancient Egyptian civilization, Persian civilization, Greek civilization, Roman civilization, Medieval civilization, Chinese civilization, Indian civilization, Islamic civilization, industrial civilization, and so on. Theorists of civilization have examined the dynamics of civilizations as such, looking at the cycles from barbarity to civilization to decadence. They have also looked at the relations between civilizations, which have very often been in conflict with each other.

Conceiving of modernity as a civilization originating in Western Europe, succeeding Medieval European and Renaissance civilizations, facilitates further analysis of the nature of the capitalist socio-economic formation. The civilization of European modernity emerged from a civilization that had been in almost constant struggle with and under threat of conquest by Islamic civilization, and this had brutalized Europeans [8, ch.3]. Also, Europe, unlike China, was never fully united, and Europeans were further brutalized by constant warfare between kingdoms. Europe in this regard had much in common with the period of the warring states in China, which similarly was a period of both brutality and creativity. Throughout history, the development of the forces of production was not an autonomous process, as orthodox Marxists would have it, but often has been fostered by rulers as a means to support the military [17]. The imperialism of the Europeans was an extension of this militarism. While markets developed in medieval European society, especially Northern Italy, the rise of capitalism was, as the Austrian Marxist Karl Polanyi argued, a deliberate process of dis-embedding markets from communities and then imposing markets as a way of dominating people [4]. This is what happened in Britain with the control of trade and the enclosure of the commons, leaving people with no other means to make a living other than working for others in factories. Such wage slavery was the successor to and built on the slavery instituted in Europe’s colonies. The outcome of all this was that by 1914, Europeans were in control of 85% of the world’s land surface. Imposing markets by military and political force has continued up until the present, and is clearly evident in the imposition of neoliberal economic policies around the world by the United States’ military-industrial-intelligence complex, overthrowing governments that have stood in the way of this, as William Blum [3] and Michael Hudson [21] have convincingly argued.

It is important to recognize that this civilization was not monolithic, however. Mainstream capitalist modernity was associated with atomism (including atomic, possessive individualism) and mechanicism, imposed and then promulgated through the categories of economics, the categories serving as forms of life that Marx was critiquing. However, such thinking succeeded the Renaissance committed to reviving social relations and forms of thinking developed in Ancient Greece and Republican Rome. This tradition survived and was further developed as the Radical Enlightenment in opposition to the dominant institutions and forms of thinking of capitalism [22]. This culminated in the German Renaissance of the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries [36]. This was strongly influenced by Leibniz who in turn was influenced by Chinese neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi, but was greatly developed with the philosophies of Kant and his students, most importantly, Herder and Fichte.

Herder developed the notion of cultures and a conception of humans as essentially cultural beings participating in a dynamic nature, expressing themselves and realizing their own unique potentialities in this context. Different societies and civilizations were then characterized by their different cultures, and Herder called for respect for these, but also argued that there is an evolution of successive cultures towards greater humanity. Fichte also argued that there is moral progress through history driven by the quest for recognition leading to more and more adequate recognition by people of each others’ freedom and significance. Synthesizing the work of Herder and Fichte, Hegel developed a conception of history as consisting of both cycles and successions of civilizations, with later civilizations advancing civilization not only through more adequate recognition, but also more adequate representation and tools or technology. He referred to this as the development of Spirit rather than culture, but this was just a terminological difference. Schelling held similar views, but called for the development of a post-Newtonian physics, new forms of mathematics adequate to life and humanity, and proper appreciation of the significance of life as such. He also saw modern history as leading to the unification of the world through the market paving the way for a world-consciousness, overcoming the parochialism of particular civilizations, and creating global institutions to prevent wars. This would be a global civilization. Because of Schelling’s later conservatism, Marx dissociated himself from and then ignored Schelling, but his vision of communism was really upholding this notion of a global civilization, building on the achievements of past civilizations but going beyond them to create a classless society free from the enslavement of people by ruling classes, and free from imperial domination, and as eco-Marxists have shown, free from destructive exploitation of nature.

Situating Marx’s work in this way enables it to be formulated as the quest to create a global civilization based on rejecting and replacing, or at least, greatly modifying the culture of modernity and its embodiment in the dominant institutions and forms of thinking. Most importantly, this is the hierarchically organized world-system described by Wallerstein and Bunker. However, this will involve building on the achievements of past civilizations, including Greek civilization, the German Renaissance and some achievements of the civilization of modernity with its scientific and technological advances, and also the institutions developed to contain this civilization’s oppressive and destructive tendencies. This can now be seen to include the notion of rule of law, including international law, the United Nations, various forms of socialism subordinating markets to the common good of communities, and post-mechanistic science. Post-mechanistic science, inspired by the German Renaissance, can uphold a different understanding of humans and their relations to each other and to the rest of nature, of the place of humanity within nature, and of the potential of humanity to change these relations.

Marx’s main work can be seen as advancing a major part of this project, critiquing the categories of political economy, the forms of existence which still dominate the world. He was paving the way for their replacement by categories developed by Herder, Fichte, Hegel and Schelling, among others, but this only became evident from his unpublished writings, and this replacement requires a broader project of replacing the categories defining physical existence in the sciences and the humanities (undertaken to some extent by Friedrich Engels).

Developing an ecological culture

As the Russian philosopher, Alexander Bogdanov, argued, overcoming capitalism has to be associated with creating a new culture that absorbs the best of all past cultures. While a new conception of the economy is required for this, what is at least as important is the development of a new conception of nature replacing the atomistic, mechanistic view of nature, a conception of nature which enables humans to be understood as essentially cultural beings but at the same time as participants in the dynamics of nature. Bogdanov aligned himself with developments in thermodynamics, an area of science largely inspired by Schelling [16, p. 9], and developed a general theory of organization, or Tektology on this basis, designed to provide a monistic worldview, allowing us to see ourselves as self-organizing participants in a self-organizing universe. This was a precursor to post-reductionist systems theory and complexity theory [12]. Through this work, Bogdanov was able to predict a global ecological crisis, and the importance of avoiding this, and his work supported Vernadsky’s notion of the biosphere and provided support for the development of ecology in the 1920s in the Soviet Union.

On the basis of recent advances in thermodynamics and complexity theory, Ilya Prigogine [31, p. xiif] claimed that 'we are in a period of revolution ‐ one in which the very position and meaning of the scientific approach are undergoing reappraisal ‐ a period not unlike the birth of the scientific approach in ancient Greece or of its renaissance in the time of Galileo.' Prigogine and Stengers [32, p.68] argued that this would bring about a new alliance between science and the humanities. The furthest development of complexity theory has taken place in ecology. Ecology is the study of biotic communities, now usually characterized as ecosystems. Major advances in ecology involved appreciating the importance of recognizing symbiosis and creative emergence associated with new forms of cooperation in evolution, and the role of life in geological processes, including soil formation and changes in the atmosphere, and the central role of thermodynamics in comprehending biotic communities, or as they are now called, ecosystems. Prigogine’s work on non‐linear thermodynamics and dissipative structures along with other developments in complexity theory, including work on morphogenesis by C.H. Waddington, Joseph Needham and Brian Goodwin and the development of hierarchy theory by Howard Pattee, Timothy Allen, Stanley Salthe and Alicio Juarrero, have strengthened the anti‐reductionist tradition of ecology. Hierarchy theory is based on recognition that emergence of new levels of organization are associated with the development of enabling constraints, which in turn provide the basis for the exploration and realization of new possibilities [2, 23].

Salthe [33] has also integrated endophysics into this synthesis, the view that it is necessary to appreciate that we are part of the world we are trying to understand. Ecological concepts have been generalized, so organisms have themselves been characterized as highly integrated ecosystems. Vernadsky’s notion of the biosphere has been revived and strengthened, with Lovelock characterizing the global ecosystem as ‘Gaia’. Such work has enabled Jacob von Uexkull’s biology and Peircian biosemiotics to be integrated into ecology, generating a new sub‐discipline – ecosemiotics [25]. Vernadsky’s notion of the noosphere was reformulated by the Russian/Estonian cultural theorist Juri Lotman, building on the work of Mikhael Bakhtin, as the semiosphere, providing the basis for characterizing human cultures and institutions as semiotic phenomena [11]. These developments provide the basis for rethinking the human sciences, integrating these with the humanities through the transdiscipline of human ecology, which can then support and advance ecological economics and ecological politics as the basis for formulating public policy.

Effectively, ecology has been developed into a comprehensive world‐view based on an ontology of relational processes or inter-related patterns of activity, now able to challenge and replace the mechanistic world-view that, since the Seventeenth Century, has served as the foundation of the culture of capitalist modernity, a world-view recently revived through incorporation into it of information science [13, 16, 29]. As the theoretical ecologist, Robert Ulanowicz [35, p.6] argued in his book Ecology, The ascendent perspective:

‘Ecology occupies the propitious middle ground. … Indeed, ecology may well provide a preferred theatre in which to search for principles that might offer very broad implications for science in general. If we loosen the grip of our prejudice in favour of mechanism as the general principle, we see in this thought the first inkling that ecology, the sick discipline, could in fact become the key to a radical leap in scientific thought. A new perspective on how things happen in the ecological world might conceivably break the conceptual logjams that currently hinder progress in understanding evolutionary phenomena, development biology, the rest of the life sciences, and, conceivably, even physics.’

What became evident through ecology is that organisms, interacting with each other, transform their environments in a way that is conducive to their life, making these whole communities resilient in the face of perturbations. They do so through creating niches that allow individuals and species to explore new possibilities and developing in new directions. Conceiving of ecosystems as biotic communities, these ‘niches’ can be equated to ‘homes’ for the emergence and flourishing of component organisms, and also component ecosystems, insofar as these augment the life of these communities. Ecosystems consist of communities of communities at multiple levels. That is, biotic communities are ‘ecopoietic’, creating the niches or homes within which components can flourish and new living forms can emerge that augment the life of these communities [12]. When they do so, they are healthy; when they damage or eliminate such niches, they are sick, lacking resilience in the face of perturbations, and prone to collapse. Humanity is part of nature, and with its development through successive civilizations is now undermining the niches where the life-forms required for the health of the current regime of the global ecosystem are being severely damaged. An ecological civilization would be a global civilization reversing this, developing by augmenting life, providing the niches or homes in which life forms, both human and non-human, that do augment the conditions for other life forms, are able to flourish.

Realising ecological civilization

The second of Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach [27] begins: ‘The question whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory but is a practical question. Man must prove the truth — i.e. the reality and power, the this-sidedness of his thinking in practice.’ I have been arguing that a global ecological civilization requires the creation and advance of a new culture based on a more adequate understanding of life and humanity, including their possibilities. Further development of this ecological conception of the world is required. But there is also the problem of how to make this conception of the world practically efficacious, not only to put these new beliefs into practice, but to embody them in practices and institutions, making these a part of a new reality, changing the organization of humanity so that people are oriented in their lives to live in a way that augments life through augmenting the lives and conditions for life of the communities in which they are participants. That is, it is necessary to prove the truth of ecological thinking in practice.

One of the most important requirements for this the development of history, that is, stories showing how nature and humanity have developed deploying this ecological perspective. It is through stories that people situate themselves in the world and in history as agents involved in creating the future. Rethinking and rewriting history is not just a theoretical project, however. It involves individuals and communities at multiple levels, including nations and existing civilizations, rethinking their place in the world and its history, reorienting themselves through their stories, defining their place in broader histories, to create the future not only of themselves and their particular communities but the future of humanity and the biosphere. It requires the development of transculturalism as this was defended by Mikhail Epstein. As Epstein characterized this [6, p.298f.]: ‘the fundamental principle of transcultural thinking and existence’ is the ‘[l]iberation from culture through culture itself’, generating a ‘transcultural world which lies not apart from, but within all existing cultures’. This is the condition for creativity in the quest for truth, justice and liberty, for as the Russian philosopher Vladimir Bibler observed, ‘Culture can live and develop, as culture, only on the borders of cultures’ [6, p.291]. I am suggesting the notion of ecopoiesis as a transcultural as well as a cultural concept provides a way of thinking that facilitates this reorientation, giving a place to while aligning diverse cultures in this project, indicating what to aim at and what kind of world we should be striving to create.

An ecological world-view requires that we take our starting point the perspective of the whole, which as Mae-Wan Ho [19] argued in relation to the evolution of life, is the biosphere. The beginnings of this evolution involved the early biosphere providing the niches or homes where various new forms of life could emerge, beginning with procaryote cells, then eukaryotic cells, then multi-celled organisms and then communities of these, creating biotic communities with ecosystems making niches for more complex organisms and their interactions, eventually providing the niches or homes which made possible the emergence of human life, and then for the development of civilizations. These in turn have provided the niches or homes for the development of various kinds of communities, institutions and cultural fields, which in turn have provided niches where individuals could develop their full potential to augment the life of these communities, and thereby of humanity. Civilizations in order to flourish had to provide homes or niches for subordinate communities and communities of communities to flourish. However, as Joseph Tainter [34] has shown, most civilizations destroyed the environmental conditions for their existence. This is what European civilization was facing in the Fifteenth Century, and this largely accounts for its subsequent imperialism. A healthy global civilization of humanity will severely limit such destructive activity and provide homes for people, both as individuals and as communities, who in their lives are augmenting the conditions for each other, including the biotic communities of which humans are part. The struggle for ecological civilization can now be characterized as the struggle for homes in which individuals and communities at all levels can flourish, in doing so, aligning themselves with the quest to provide such homes for each other and for all living beings contributing to the flourishing of the current regime of the global ecosystem which has been ideal for humans, putting an end to greenhouse gas emissions, pollution by economic wastes, and destruction of more local ecosystems and species.

This conception of the world provides the ethics, political philosophy and science required to formulate goals and policies, and to act to create this civilization. Two of the most important works in ethical and political philosophy were Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Politics, works which strongly influenced Marx [24, p.94f.]. Aristotle argued that the first principle of politics is that the polis should be organized to provide the conditions for individuals to achieve eudaimonia, that is, to achieve their full potential as human beings to live fulfilling and fulfilled lives as participants in the polis striving for its common good. This, he argued, involves developing the highest virtues through participating in the political and intellectual life of the polis. This principle can be developed and generalized through the notion of ecopoiesis to the whole hierarchy of communities and communities of communities within which people are partcipating, being committed to augmenting the conditions for life of all these communities insofar as they are involved in augmenting life [12].

‘Political’ life questing after the common good can include economic life, taking into account the health of all biotic communities, and intellectual life questing after truth and wisdom can include all cultural life, including history, literature and the arts as well as philosophy, mathematics and science [11]. Ecopoiesis as home making in this sense can be generalized to the relationship between all human communities, with broader communities having as their goal providing the homes or niches for more local communities, and this quest has to be seen in relation to these communities fostering the niches for other organisms, species and ecosystems participating in the biosphere [18].

By relating all this to ecology which incorporates thermodynamics, this generalization also provides the basis for examining power relations between individuals and communities at all levels, including those involved in major international power struggles. Building on the work of Richard Newbold Adams and Stephen Bunker on how power operates, provides guidance on how to engage in these power struggles, and also identifies what kinds of power relations are required for an ecological civilization to develop and flourish. Ecology also brings into focus the importance of developing enabling constraints in these power struggles, avoiding the tendency for power struggles to reproduce or lead to new levels and forms of oppressive and ecologically destructive domination. These should be seen as institutionalized constraints, re-embedding markets in communities, reducing markets to instruments of communities for decentralizing decision-making, while communities should be committed to augmenting the conditions for people, whether individuals or communities, to realize their full potential to augment life and the conditions for it. These conditions are the ‘homes’ of people. This is the goal of eco-socialism understood as ecopoiesis – producing the homes in which virtues are cultivated and people can flourish and develop their full human potential.

It is impossible to go into detail about all that is involved in these power struggles, but a particular example illustrates much of what is involved. This is the development of international law which can be the basis for ending the brutal struggle for power between people that is the ultimate driver of ecological destruction. The legal system is a set of institutions that constrain people’s activities, facilitating more complex organizations and actions [14]. The first legal systems involved the rule of law, as in the Legalist philosophy of the Qin Dynasty in China where the ruler controlled people through laws and severe punishments, but was not himself subject to these laws. The Ancient Greeks realized the potential of formulating their own laws as enabling constraints providing the basis for freedom. This is the original meaning of ‘autonomy’. Inspired by Aristotle, legal theorists argued that enacted laws were only genuine laws insofar as they upheld justice and commitment to the common good. International law evolved into upholding constraints on nations to allow all nations to achieve self-determination.

One of the most important developments of this, coming at the end of WWII and initially driven by the US President, Franklin Roosevelt, was setting up the institutions of the United Nations, upholding international law based on justice and opposed to colonialism. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the ruling elites of USA established a monopolar world order, reverting to rule of law, imposing law on other nations and peoples to facilitate the unconstrained exploitation of labour and resources of the entire world by transnational corporations, without USA itself conforming to these laws. This was associated with promoting and imposing neoliberalism, a doctrine rejecting any commitment to justice or the common good, freeing transnational corporations to plunder public wealth from the countries subjugated by this rule-based order [20, 21]. This has been characterized by John McMurty [28] as the cancer stage of capitalism. This monopolar world-order is now being challenged by proponents of the multipolar world, working through the United Nations, upholding the rule of law and arguing that such law should be developed to achieve ecological sustainability. This means that international law is being utilized to re-embed markets in the global community, integrating the notion of a multipolar world with the quest for an ecological civilization [18]. This is a significant challenge to the hierarchical structure of the world-system dominated by the managers of transnational corporations and their political and military allies, and an important advance in the quest for an ecological civilization.

References:

- Adams, R. N. (1975). Energy and structure: A theory of social power. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Allen, T.F.H. and Starr, T.B. (1982). Hierarchy: Perspectives for ecological complexity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Blum, W. (2014). America’s deadliest export: Democracy: The truth about US foreign policy and everything else. London: Zed Books.

- Brie, M. & Thomasberger, C. (Eds.) (2018). Karl Polanyi’s vision of a socialist transformation. Montreal: Black Rose Books.

- Bunker, S. G. (1988). Underdeveloping the Amazon: Extraction, unequal exchange, and the failure of the modern state. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Epstein, M. N. (1995). After the future. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press.

- Gare, A. (1994). Aleksandr Bogdanov: Proletkult and conservation. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 5(2): 65-94.

- Gare, A. (1996). Nihilism Inc.: Environmental destruction and the metaphysics of sustainability. Sydney: Eco-Logical Press.

- Gare, A. (2000). Aleksandr Bogdanov's history, sociology and philosophy of science. Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science, 31(2): 231-248.

- Gare, A. (2002). Human ecology and public policy: Overcoming the hegemony of economics. Democracy and Nature, 8(1): 131-141.

- Gare, A. (2009). Philosophical anthropology, ethics and political philosophy in an age of impending catastrophe. Cosmos & History, 5 (2): 264-286.

- Gare, A. (2010). Toward an ecological civilization: The science, ethics, and politics of eco-poiesis. Process Studies, 39(1): 5-38. (Chinese translation in Marxism and Reality, 8(1): 191-202).

- Gare, A. (2011a). From Kant to Schelling to process metaphysics: On the way to ecological civilization. Cosmos & History, 7(2): 26-69.

- Gare, A. (2011b). Law, process philosophy and ecological civilization. Chromatikon VII sous la direction de Michel Weber et de Ronny Desmet, Louvain-la-Neuve: Les Éditions Chromatika: 133-160.

- Gare, A. (2012). China and the struggle for ecological civilization. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 23(4): 10-26.

- Gare, A. (2013). Overcoming the Newtonian paradigm: The unfinished project of theoretical biology from a Schellingian perspective. Progress in Biophysics & Molecular Biology, 113(1) Sept.: 5-24.

- Gare, A. (2020). After neoliberalism: From eco-Marxism to ecological civilization. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 32(2): 22-39.

- Gare, A. (2024). Rethinking political philosophy through ecology and ecopoiesis. Ecopoiesis: Eco-human Theory and Practice, 5(2): 6-24.

- Ho, M.-W. (1988). Gaia: Implications for evolutionary theory. In Peter Bunyard and Edward Goldsmith (Eds.), Gaia, the thesis, the mechanisms and the implications. Wadebridge, Cornwall: pp. 87-98.

- Hudson, M. (2005). Global fracture: The new international economic order. London: Pluto Press.

- Hudson, Ml. (2022). The destiny of civilization: Finance capitalism, industrial capitalism, or socialism. Islet Verlag.

- Jacob, M. C. (2003). The radical enlightenment: Pantheists, freemasons and republicans, [1981], 2nd ed. The Temple Publishers.

- Juarrero, A. (2023). Context changes everything: How constraints create coherence. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- MacIntyre, A. (2016). Ethics in the conflicts of modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maran, T. (2020). Ecosemiotics: The study of signs in changing ecologies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marx, K. and Engels, F. (1978). Manifesto of the Communist Party’. In Robert C. Tucker (ed.), The Marx-Engels reader, 2nd ed., New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Marx, K. (2002). Theses on Feuerbach. Marxists Internet Archive. file:///C:/all/EcoCiv/Theses%20On%20Feuerbach%20by%20Karl%20Marx.htm (viewed 15th Sept. 2024).

- McMurty, J. (2013). The cancer stage of capitalism. 2nd ed. London: Pluto Press.

- Moore, J. W. (2015). Capitalism in the web of life: Ecology and the accumulation of capital. London: Verso.

- Patel, R. & Moore, J. W. (2018) History of the world in seven cheap things: A guide to capitalism, nature, and the future of the planet. Oakland CA: University of California Press.

- Prigogine, I. (1980). From being to becoming: Time and complexity in the physical sciences. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

- Prigogine, I. and Stengers, I. 1984. Order out of chaos. New York: Bantam Books.

- Salthe, S. (2005). The natural philosophy of ecology: Developmental systems ecology. Ecological Complexity, 2: 1-19.

- Tainter, J. A. (1988). The collapse of complex societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ulanowicz, R. E. (1997). Ecology: The ascendent perspective. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Watson, P. (2010). The German genius: Europe’s Third Renaissance, The Second Scientific Revolution and the Twentieth Century. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Young, R. M. 1985. Darwin’s metaphor: Nature’s place in Victorian culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reference for citations

Gare, A. (2025). The theoretical foundations of socialist eco-civilizational progress. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, 6 (1). [open access internet journal]. – URL: http://en.ecopoiesis.ru (d/m/y)